By Iris Ho and Bruce Guthrie on behalf of all authors

Measuring multimorbidity is complex. We have recently published papers from a Health Data Research UK funded study which report a systematic review of how multimorbidity is measured in the literature, and an international Delphi study seeking to identify consensus on how multimorbidity should be measured.

The systematic review examined how 566 studies defined and measured multimorbidity, finding very large variation. One in eight studies did not report which conditions were included in their multimorbidity measure. Where reported, then the number of conditions included varied from two to 285 (median 17, IQR 11-23). Most studies included at least one cardiovascular condition (98%), metabolic condition (97%), respiratory condition (93%), or musculoskeletal condition (88%). Only 78% included any mental health condition, and many other body systems were infrequently included (eg haematological conditions 24%). Only eight individual conditions (all of them physical conditions) were included by more than half of studies (diabetes, stroke, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure). (Ho et al https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(21)00107-9/fulltext).

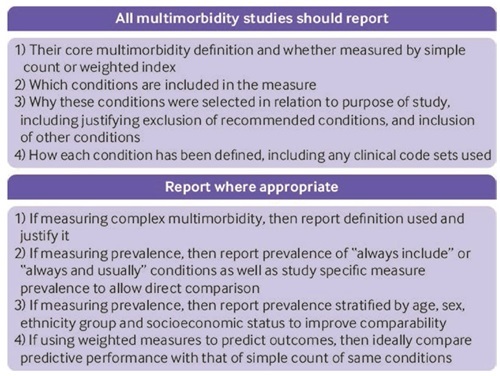

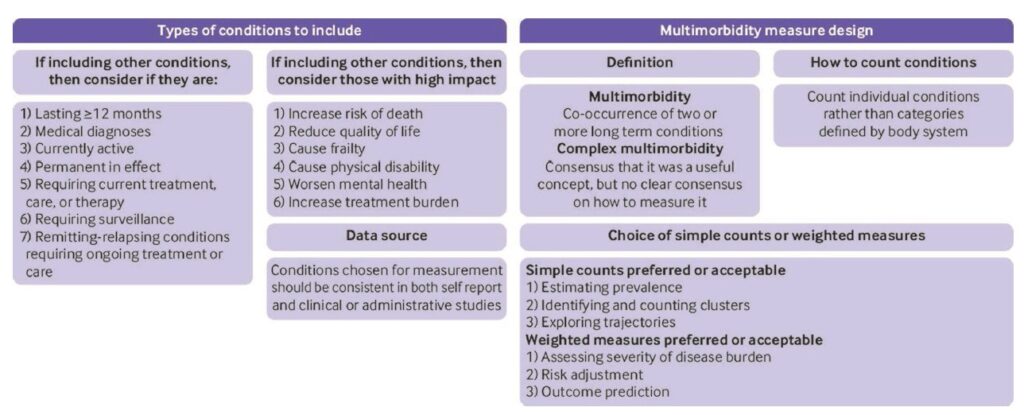

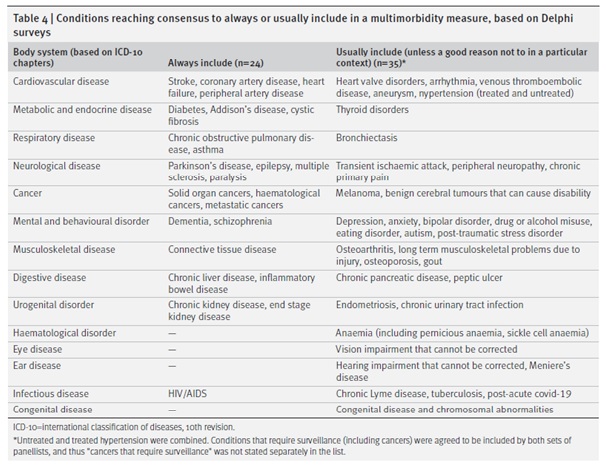

We concluded that there was an urgent need for more consistency in the field, and therefore carried out a three round Delphi consensus study with 150 professionals and 25 public panel members in round 1. Highlights of the results were that there was consensus that multimorbidity should be defined as two or more conditions. Although ‘complex multimorbidity’ (eg 3+ conditions, or 3+ conditions from 3+ body systems) was perceived as potentially useful, there was no consensus on how to define it, highlighting the need for more research into alternative definitions. Simple counts of conditions were preferred for estimating prevalence and examining clusters or trajectories, and weighted measures were preferred for risk adjustment and outcome prediction. Reflecting the variability in the systematic review, there was consensus that studies needed to be more consistent in their reporting (figure and table below are reproduced from the paper under the CC-BY licence).

Finally, there was consensus for 24 conditions that should “always” be included in multimorbidity measurement and 35 that should be “usually included (unless a good reason not to in a particular context)”. We recognise that choices should reflect context and local condition prevalence so the combined ‘always or usually include’ list can be seen as a core set of conditions with scope for local adaptation (Ho et al https://bmjmedicine.bmj.com/content/1/1/e000247).

Further research and consensus is needed to define codelists or other diagnostic criteria for the listed conditions, to examine the relative value of unweighted vs weighted measures, and to understand the additional value (if any) of different definitions of complex multimorbidity.

Like all consensus recommendations, we expect that many researchers will find at least a few items that they disagree with. BG for example finds the non-inclusion of depression in the ‘always include’ list perplexing (albeit it only just failed to reach the pre-specified 70% consensus level for inclusion, but easily reached consensus for ‘usually include’). However, unless there are pressing and explicitly justified reasons to vary from the consensus, we think it would ideal for researchers in this field to align where feasible. We hope that these studies will be interesting and useful to the research community, and welcome any feedback.