By Jonathan Stokes

There is a lack of evidence on effective intervention for managing patients with multimorbidity. A major barrier to progress in this area is the lack of consensus over how best to describe models of care for multimorbidity. If evidence is to drive clinical innovation, we need to build the evidence base through ongoing evaluation and review. That process is hampered, however, by incomplete descriptions of models in publications. Without accurate descriptions, researchers cannot replicate studies or identify ‘active ingredients’. There have been many examples in recent years of reporting frameworks that have improved the utility of health services research (http://www.equator-network.org/). In this paper [1], we describe a framework as a starting point for addressing this need in the high-profile area of multimorbidity.

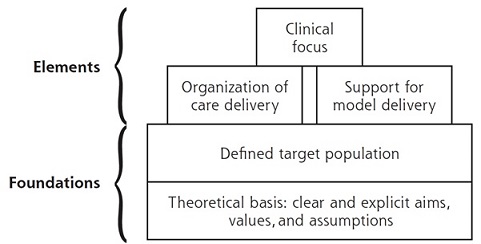

Our framework describes each model in terms of the foundations:

• its theoretical basis (i.e. the clear and explicit aims, values and assumptions of what it is trying to achieve)

• the target population (‘multimorbidity’ is a somewhat vague term, so there is the need to define the group carefully, e.g. a patient with diabetes and hypertension might have very different care needs than a patient with dementia and depression)

• the elements of care implemented to deliver the model

We categorised elements of care into 3 types: (1) clinical focus (e.g. a focus on mental health), (2) organisation of care (e.g. offering extended appointment times for those who have multimorbidity), (3) support for model delivery (e.g. changing the IT system to better share electronic records between primary and secondary care).

Using the framework to look at current approaches to care for multimorbid patients, we found:

• The theoretical basis of most current models is the Chronic Care Model (CCM). This was initially designed for single disease-management programmes, and arguably not sensitive to the needs of multimorbidity.

• That current models mostly focus on a select group, usually elderly or high risk/cost. It is important to remember that in absolute terms, there are more people with multimorbidity aged under 65 years. Similarly, high risk patients are an obvious target, but there may be too few of them to make a significant impact on overall system costs. It is important that models incorporate the needs of younger and (currently) lower risk/cost patients (potentially with most scope for effects of preventing future deterioration).

• There is a need for increased attention for low-income populations (where multimorbidity is known to be more common), and for a focus on mental health (multimorbid patients with a mental health issue are at increased risk for detrimental outcomes).

• The literature suggests that the large emphasis in current models of care on self-management may not always be appropriate for multimorbid patients who frequently have barriers to self-managing their diseases. The emphasis on case management (intensive individual management of high-risk patients) should take into account the evidence that while patient satisfaction can be improved, cost and self-assessed health are not significantly affected.

We also looked at how approaches have changed over time, comparing newer to older models. Newer models tend to favour expansion of primary care services in a single location (e.g. increased co-location of social care services and extended chronic disease appointments), rather than coordination across multiple providers or at home (e.g. decreased care planning and integration with other social and community care services, decreased home care).

Health systems have only recently begun to implement new models of care for multimorbidity, with

limited evidence of success. Careful design, implementation, and reporting can assist in the development of the evidence base in this important area. We hope our framework can encourage more standardised reporting and research on the theoretical basis and target population for interventions, as well as the contribution of different elements (including interactions between them) needed to provide cost-effective care and support redesign of health systems for those who use them most.

This free to read article can be found at the following link:

http://www.annfammed.org/content/15/6/570.full

[1] Stokes J, Man M-S, Guthrie B, Mercer SW, Salisbury C, Bower P. The Foundations Framework for Developing and Reporting New Models of Care for Multimorbidity. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2017;15(6):570-7.